Introduction: Fashion and Biodiversity

The Fashion Values Methods are short-form learning resources that provide a spotlight into topics focused on fashion and nature. Aimed at designers, students, graduates, and fashion professionals, they’re open to anyone with an interest in fashion and sustainability. Each Method takes approximately 30 minutes to read through, and introduces you to the core issues, impacts, and industry contexts for each topic.

1/18

The Fashion Values Methods approach each topic from a regenerative perspective: looking at practices, innovations and mindsets that restore and renew our ecosystems through fashion.

If this Method sparks your curiosity and you’re interested in an in-depth learning experience, register now for Fashion Values: Nature, our free, four-week online course.

__

Welcome to the ‘Introduction: Fashion and Biodiversity’ Method, a spotlight on the relationship between fashion and biodiversity. The Method is structured into five sections:

Section 1: An overview of fashion and biodiversity, including key definitions and facts, why fashion needs biodiversity, and how fashion currently impacts biodiversity.

Section 2: An ‘in conversation’ with Kering and CSF on Kering’s approach to biodiversity.

Section 3: A look at five different ways fashion can support biodiversity.

Section 4: Industry examples of how brands are addressing biodiversity.

Section 5: Some critical questions to help you starting thinking about biodiversity in your own practice.

This Method will help you begin to:

Understand the relationship between fashion and biodiversity.

Recognise challenges, gaps and opportunities in this relationship.

Gain insight into the work done by Kering and other brands in this area.

Understand how you can begin to address biodiversity and nature in your own work.

This Method was authored by Centre for Sustainable Fashion with support from global luxury group Kering. Faced with increasing biodiversity loss, change and other environmental threats to long-term survival, Kering has an alternate vision for the future of fashion. Their biodiversity strategy isn’t about minimising harm or trying to reduce negative impacts. They want to develop supply chains and practices that make a positive impact.

“How we solve the ongoing environmental crisis is likely the biggest challenge facing our generation. Given the scale of biodiversity loss sweeping the planet, we must take bold action. As businesses, we need to safeguard nature within our own supply chains, as well as champion transformative actions far beyond them to ensure that humanity operates within planetary boundaries.” — François-Henri Pinault, Chief Executive Officer, Kering

2/18

1.1 What is biodiversity? Why does it matter?

Biodiversity or biological diversity is defined by the United Nations as "variability among living organisms from all sources including, among other things, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are a part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems”.(1)

To put it in simple words, biodiversity means ‘living nature’; the living skin across the whole world, including animals, plants, the habitats and ecosystems they live in, and how they interact with each other. Our skin holds us together, enables us to breathe and move, to create and to interact in the world.

While extinction of species is a natural process, it is estimated that the current rate of biodiversity loss is one thousand times higher than the natural rate.(2),(3) The recent report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) warns that the loss of species and global decline of natural systems is accelerating at a rate unprecedented in human history.(4)

Biodiversity loss severely impacts the health of entire ecosystems, and consequently also the human ability to adapt to the changing environment. As a result, “we are eroding the very foundations of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide”.(5)

3/18

1.2 Key Facts and Indicators

8 million: total estimated number of animal and plant species on Earth(6) 1 million: total estimated number of species threatened with extinction 75%: land environment “severely altered” by human actions 66%: marine environment “severely altered” by human actions 1000 x: current rate of biodiversity loss compared to the natural rate

Five direct drivers of change in nature, in order of relative global impact:(7)

Changes in land and sea use

Direct exploitation of organisms

Climate change

Pollution

Invasive alien species.

Indicators used for the measurement of biodiversity health:(8)

Species richness

Population number

Genetic diversity

Species evenness

Phenotypic variance

Further biodiversity reading: UN Environment Programme (2015). Biodiversity A-Z. International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species (2019). E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation (n.d.). Half-Earth Project.

4/18

1.3 Why is biodiversity important to fashion?

“Every element of what we wear comes from nature” — Professor Dilys Williams, Director of Centre for Sustainable Fashion, UAL

Biodiversity, ‘living nature’, is the living skin across the whole world, including animals, plants, the habitats and ecosystems they live in, and how they interact with each other. Nature is an entity in its own right, and not just a resource to be used by the fashion industry.

Everything we wear – garments, accessories, jewellery, footwear – is made from materials found in the world around us.(9) Fashion has a basic role to clothe society, and draws from nature both as a source of aesthetic inspiration and of raw materials: we make fashion derived from plants, animals, insects, oils, minerals, metals. We design florals, leaf prints, landscapes, skeletons inspired by nature, and created from its resources. A biodiverse ecosystem gives fashion an incredible palette to draw from.

Growing, processing and innovating with biodiverse species has given fashion all of its materials: cotton, linen, bast fibres, regenerated cellulosics, silk, lotus fibre, leather, fur, animal skins, wool, cashmere, mohair, angora, feathers, muka, tapa cloth, indigo, madder, bark dye, bio-plastics, orange fibre and fish skin, among many others. Even materials not derived from living species – such as oil-based synthetics or metals – are extracted from environments that support biodiversity.

But the relationship between fashion and nature is complex: on the one hand, there is fashion’s intention to celebrate nature, on the other, much of the industry’s production involves dangerously negative effects.

5/18

1.4 How does fashion impact biodiversity?

While fashion relies on biodiversity, it is also responsible for accelerating biodiversity loss. Fashion 'takes’ from nature, using it as a bank of resources – and the fashion industry has built up an enormous debt that is being repaid with consequences it can’t always predict. Some of the critical negative impacts of the fashion industry include contributing to soil and land degradation, deforestation, desertification, land conversion and pollution, declines in plant and animal populations, and much of what we take from nature is processed in ways that prevent it from being returned to the earth.(10)

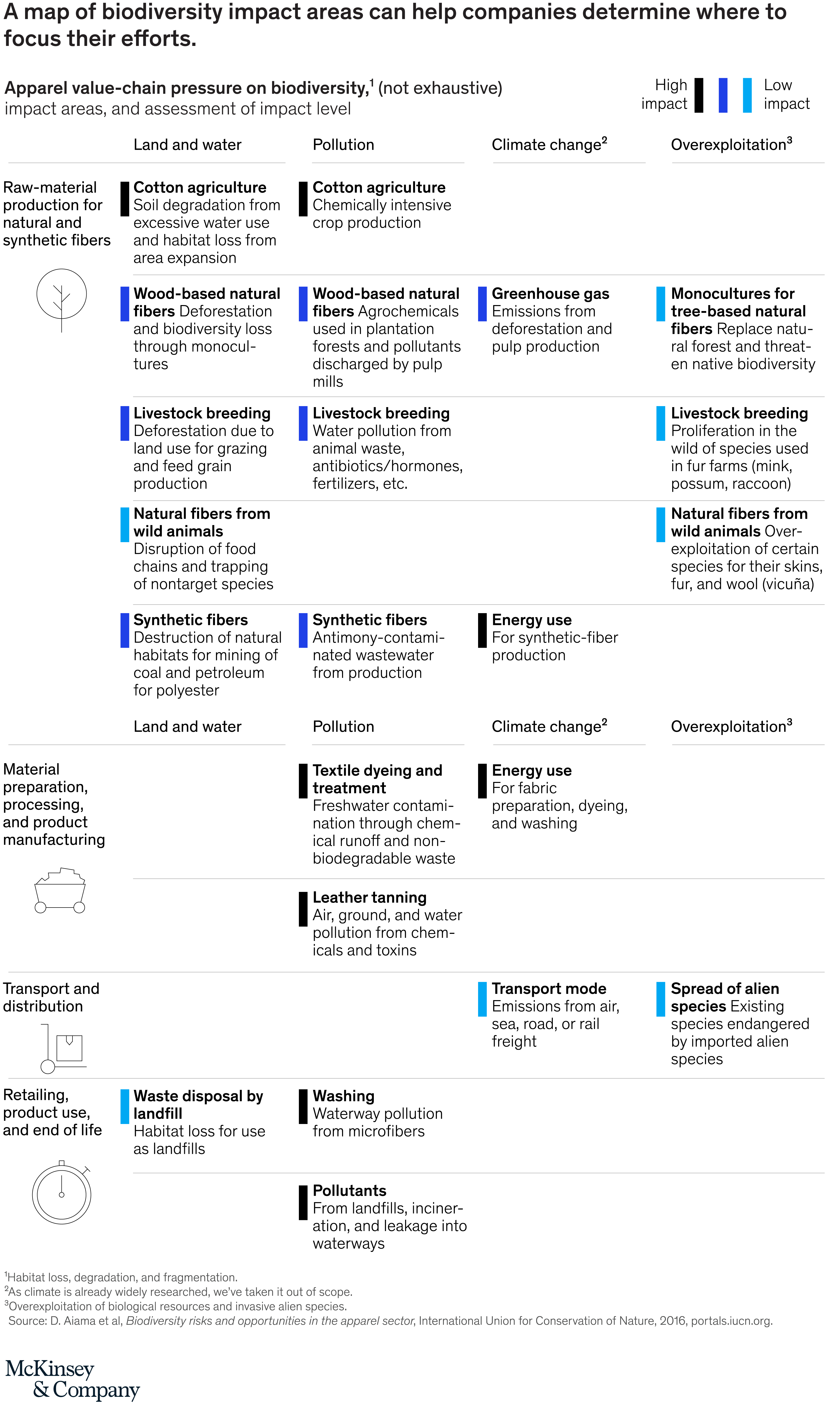

A recent report from McKinsey and Company has determined that “Most of the negative impact on biodiversity comes from raw-material production, material preparation and processing, and end of life.”(11) Their table maps these impacts:

In this section, we explore three types of biodiversity impacts related to fashion: planetary impacts, material impacts, and waste. These encompass both systemic effects – those caused by the fashion industry as a whole – and the effects of specific fashion processes and choices, such as material use.

Though this section looks at some of the core negative effects fashion has on biodiversity, it’s important to acknowledge that these aren’t always black and white. Fashion’s impacts on nature are complex, interwoven with other industries, and not easily attributable to a clear cause-and-effect. This is an introduction to the relationship between fashion and biodiversity, and not an exhaustive list.

In section two and three, we’ll go on to explore alternative practices that address the below and can help to make the change from extractive to regenerative.

Planetary impacts: fashion and population declines

The biggest impact of the fashion industry on biodiversity stems from habitat loss, which which can indirectly pose a significant risk to several species (such as snow leopards, ibex, golden eagles and boreal owls).(12) The prevalence of monocultural systems (where only one crop is grown on a large scale), which is the dominant agricultural method for crops such as cotton, also has negative impacts on biodiversity at ecosystem scales.

Planetary impacts: soil degradation

Soil is one of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems, and yet scientists have alerted us that the world’s topsoil can support only another sixty crop harvests if we continue to use the current farming practices – including widespread chemical use, planting monocultures, excessive tilling, and land conversion to agricultural use.

Material impacts: conventional cotton

Conventional cotton is the natural material most used in fashion production, which makes up a third of all the textile fibres. Conventional cotton is also detrimental for natural habitats when it is cultivated – especially in monoculture – to replace indigenous vegetations. The intensive use of pesticides has caused biodiversity in soil and pollinator populations to decrease. Cultivation of cotton covers 2.4% of the all the crop land in the world, yet involves 22.5% of the insecticides used worldwide, and requires significant volumes of water compared to other fibres.(13)

Material impacts: conventional wool and cashmere

Wool and cashmere are contributing to habitat loss and soil degradation at an unprecedented pace. Overgrazing of livestock for wool and other fibres affects the balance of plant species, with an increase of grass-like plants and decrease of woody shrubs and trees. Most grasslands in Mongolia have already been degraded or are turning into deserts due to cashmere over-grazing practices.

Material impacts: leather and viscose

Leather and viscose are two of the main causes of biodiversity loss related to fashion materials, causing deforestation in precious ecosystems and protected forests, including the Amazon, Indonesia and North America. More than 150 million trees are cut down annually to derive viscose fibres, and many of these are taken from at-risk, old-growth forests (rather than managed tree plantations, where they’re grown for the purpose of harvest). In fact, it takes up to 4.5 tons of trees to make 1 ton of viscose,(14) and the chemicals used to process wood into fibre can create water and soil pollution, which increase habitat loss.

Cattle ranching - which produces products ranging from meat to dairy and leather, is also one of the main causes of deforestation. The livestock industry uses approximately 80% of the global agricultural lands, and the 2019 Amazonian wildfires are in part attributable to deforestation for Brazilian cattle farming(15). The livestock industry also causes water pollution, creating dead areas in coastal areas and degradation of coral reefs.

Waste

Waste generated by fashion production – from raw materials production, to processing and manufacture, to end of life – includes chemical runoff, liquid waste, addition to landfill and microfibres. These three waste streams serve to pollute waterways, air and land, poison aquatic life, contribute to habitat loss, and present enormous challenges in marine environments.

Waste: chemicals

Textile production and processing have significant environmental impacts, including overexploitation of freshwater resources, use of hazardous chemicals, nonbiodegradable liquid waste, and chemical pollution of waterways and surrounding land. 25% of global industrial water pollution can be attributed to textiles production.(16) For further information, see the Greenpeace Detox campaign.(17)

Waste: microfibres

Microfibres are fibres smaller than 5mm in length which are shed during textile production, garment manufacture, laundering, wear and after disposal. Both natural and synthetic textiles shed microfibres, though some microfibres are able to biodegrade (such as plant-based fibres that have been treated with non-toxic chemicals that don’t prevent decomposition). Those that can’t – in particular plastic microfibres – are recognised as a major source of plastic pollution.(18)

Waste: textiles and apparel

Textile offcuts and unsold or discarded garments are rarely recycled or reused. Approximately 87% of the total fibre input used for clothing is incinerated or ends up in landfill.(19) This has implications for biodiversity, stemming from land conversion, soil fertility and air pollution from both incineration and landfill.(20)

__

Fashion – as an industry, as a culture and as a system – must recognise its interdependency with nature and biodiversity. If we continue extracting natural resources, polluting ecosystems, and accelerating biodiversity loss at the current rate,the very foundations of the fashion Industry are at risk.

It is imperative that these negative impacts must be addressed across the entire fashion system: from farmers, textile mills and manufacturers designers, brands and retailers, recyclers and remakers or resellers, to individuals who wear clothing. Fashion must shift to a regenerative approach – one that restores “the capability of ecosystems to self-regulate and self-maintain and so adapt to change and interference.”(21)

This is not an easy journey to make, and the industry faces challenges including pervasive consumerist cultures, economic growth imperatives and overproduction, lack of nature-focused infrastructure and policies, and lack of resources to undertake or invest in regenerative R&D, among others.(22)

Kering’s approach is to break the journey down into four stages: Avoid, Reduce, Restore & Regenerate, Transform in order to have a positive impact on biodiversity. With its long track record of environmental programming and sustainable sourcing, coupled with new ambitious commitmnets, Kering demonstrates the need to go beyond mere awareness raising, and is spearheading practices that are transformational and radical.

The next two sections look at some of the ways we can begin to make the shift from extractive to regenerative through these transformative stages: firstly, a behind-the-scenes look at the Kering approach; secondly, an overview of five different strategies that move towards regenerative practice.

6/18

2. Kering and Biodiversity: In Conversation

In this video, Dr Francesco Mazzarella, CSF’s Research Fellow in Fashion and Design for Social Change, speaks with Dr Katrina ole-MoiYoi, Sustainable Sourcing Specialist at Kering. They explore the relationship between biodiversity and fashion, and how Kering aims to make a positive impact.

Hear more about Kering’s definitions, priorities and approach to biodiversity in this video.

7/18

3. Fashion Practice to Support Biodiversity

There are many different ways fashion can start to reverse its destructive relationship with biodiversity, instead looking to enable preservation and restore damaged ecosystems. These include – among others – ecosystem conservation, restoring the health of working agricultural lands, providing farmers with economic incentives for good practices, institutionalizing carbon emissions reductions, mainstreaming traceability and blockchain, and promoting certifications and holistic management.

We’ve explored five examples that can be considered no matter where you are in the fashion system. This is not an exhaustive list, but a profile of some of the ways fashion can support biodiversity.

8/18

3.1 Impact assessment and strategies

The first step of Kering’s biodiversity commitment, as noted by Dr Katrina ole-MoiYoi in the video above, was to measure existing impacts on key species and ecosystems.(23) By following their methodology and developing impact measurement tools and environmental indicators for the business, other brands are able to develop more specific goals, commit to them and report accordingly. For example, in order to assess the impacts of their products on nature and biodiversity, companies could measure the services that nature would no longer be able to provide due to practices of the fashion industry (e.g. cotton agriculture or cattle farming) that hamper these ecosystems (e.g. provision of fresh water).

Although direct impacts on biodiversity are difficult to evaluate – especially for smaller brands – lifecycle assessments (LCAs) aim to measure the environmental impacts of fashion-specific materials or materials derived from animals raised for the food industry (like beef cattle). Tools and resources provided by Textile Exchange, Canopy or Sustainable Apparel Coalition are recognised by many parts of the sector, including NGOs and educators, as highly valuable reference points.

Industry examples:

The Kering Environmental Profit & Loss (EP&L) account is an open-source business management tool that supports companies in making an in-depth analysis of their environmental impacts. The EP&L methodology covers all tiers in the supply chain, from own operations and retail stores, through assembly and manufacturing, to processing and production of raw materials. Each tier is assessed across six impact areas: greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, water use, generation of waste, water pollution, air pollution and land use.

How can others start this process?

For students and graduates:

Look at mapping your impact on an individual, personal scale. Start with tools like World Wildlife Fund’s Environmental Footprint Calculator or the Global Footprint Network’s Footprint Calculator to see how your day-to-day life impacts the planet.

Look at mapping your fashion footprint with tools like ThredUp’s Fashion Footprint Calculator.

For designers, fashion professionals and smaller brands:

Review existing assessment tools, methodologies or frameworks including B Corp’s impact assessment tool, Cradle to Cradle’s Self-Check, the Kering EP&L and the Higg Index for their suitability to your brand.

9/18

3.2 Biodiversity Strategy

Once impacts have been assessed, a wider strategy can be built to define targets, indicators and priorities. New industry frameworks such as the below are in development to aid companies in making informed decisions, develop corporate biodiversity strategies, and create new and compelling narratives around nature-positive products.

Industry examples:

The Biodiversity Primer, co-published by Kering, Biodiversify and the University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, is a flexible framework that can be applied to make informed decisions about the mitigation of impacts on biodiversity at diverse scales. The framework consists of an eight-step process, guiding brands from identifying motivations all the way through to implementing, monitoring, learning and delivering.

The Good Growth Company in the USA is creating holistic, integrated, regenerative business systems aimed at restoring the environment and communities – for instance building non-extractive value chains for yak wool in Mongolia and developing artisanal productions.

How can others start this process?

For students, graduates, designers, fashion professionals and smaller brands:

Outline your personal vision and commitment to biodiversity in a fashion manifesto. CSF’s online course Fashion and Sustainability includes an activity on how to develop your own.

The CFDA’s Sustainable Strategies Toolkit includes a chapter on how to develop a company sustainability strategy. How will biodiversity be addressed within your strategy?

10/18

3.3 Sourcing and Diversifying Fibres

In order to reduce stress on ecosystems, students, designers and brands can diversify the fibres they use – including fibres from renewable sources, agricultural waste and recycled materials – and look to develop sourcing policies that set environmental standards.

Brands can embed their biodiversity ambitions into their sourcing strategy by switching to certified materials* rather than conventional options; or by developing policies that ban fibres from high-risk sources (such as ancient or endangered forests) and set targets for sourcing more sustainable materials.

Diversifying the fibre basket implies a shift of approach from one that starts from sourcing materials that meet particular design requirements towards another design approach which is rather driven by a consideration of the different characteristics of available natural materials. This signifies a switch from human-centric to nature-centric design. Brands can instead build a portfolio or library of nature-positive materials.

*Certifications are available for organic fibres, regeneratively farmed fibres, recycled fibres, safe chemical use, and/or environmental and social standards, among others.

Industry examples:

Canopy has launched the Next Generation Action Plan to replace 50% of the global pulp supply for viscose and paper with alternative fibres, such as agricultural residues that are currently burned and cotton textile waste that is currently landfilled.

Brazilian brand Farfarm is testing growing fibres native to Brazil (such as jute, pineapple, banana and ramie) in agroforestry systems. By incorporating trees onto the farms, trees can improve the health of the soil and provide habitat for wildlife.

Stella McCartney have banned viscose sourced from ancient or endangered forests.

Kering has created an open-source set of raw material standards, providing detailed analysis of particular best-in-class production methodologies

How can others start this process?

For students, graduates, designers and fashion professionals who are involved in materials sourcing:

Look at choosing certified lower-impact materials – such as those certified by Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS), Organic Content Standard (OCS), or Global Recycled Standard (GRS), Leather Working Group or the Responsible Wool Standard.

Phase out or eliminate non-renewable options, conventional cotton, synthetics and regenerated cellulosics.

Develop a portfolio or materials library of less common fibres or native plant-based fibres, decreasing the use of cotton, polyester, viscose and nylon.

Move sourcing and materials selection to early in the design process, so that designs respond to materials rather than driving material choice.

11/18

3.4 Regenerative farming and wildlife

Regenerative agriculture(24) is a farming method that combines conservation and rehabilitation practices to restore, renew, and revitalize agricultural land in ways that recognize and value the mutual interdependence of all human and natural systems. Practices include regeneration of topsoil and enhancing soil fertility; intercropping (growing multiple crops in close proximity), improving water cycles; capturing carbon in soil, improving carbon capture through better feedstock and better livestock management, strengthening resilience to climate change; increasing yields over time; focusing on animal welfare; revitalizing connections between farms and their surrounding communities; and protecting biodiversity both on and off the farm.

Industry examples:

The Nature Conservancy has implemented a holistic animal grazing approach for sheep in the Patagonia region of Argentina and Chile, giving positive effects on the regrowth of grasslands and the regeneration of biodiversity in the region.

The Wildlife Friendly Enterprise Network is collaborating with producers of mohair, cashmere, raffia and wool with the aim of fostering farming practices which are not only regenerative but also wildlife friendly, enabling wildlife and ecosystems to thrive.

The Savory Institute’s Land to Market programme supports the regenerative production of raw materials using the Ecological Outcome Verified EOV methodology and bringing regenerative practices to the forefront of the fashion industry.

How can others start this process?

For students, graduates, designers and fashion professionals who are involved in sourcing:

Source (or ask your textiles suppliers to source) from farms or suppliers that are certified by a regenerative standard, such as the EOV or Regenerative Organic Certified standard.

For those who are purchasing fabric at retail stores (rather than wholesale), ask your fabric retailers if they currently source any certified regenerative materials, and if not, whether this is an option.

12/18

3.5 Design and product development

Integrating biodiversity considerations into the design process begins to re-orient our priorities from a human-centric to a nature-centric approach. To put it simply, this is design that asks ‘what does nature need’ as a starting point, prioritising ecological needs over human needs (linking aesthetics, price point and availability to environmental criteria).

From this perspective, circular design strategies (e.g. those aimed at designing out waste, keeping products in use, and regenerating natural systems(25)) cannot be implemented if products have not been designed and developed in a way to enable this.

Fashion’s main impacts (as detailed in section 1.3 above) can be mitigated at each stage of the product lifecycle:

Raw materials:

Diversify the fibres that you use and select less common choices.

Switch to fibres farmed with organic and/or regenerative practices.

Look at other lower-impact materials that use less water, chemicals, energy or land than conventional choices. These might include recycled fibres or innovative textiles like bio-based synthetics.

Textile processing:

Eliminate use of hazardous chemicals – ensuring compliance with ZDHC’s Restricted Substance List and Wastewater Guidelines is a great way to utilise an existing framework. You may also look for standards that certify safe chemical use, such as, bluesign®, OEKO-TEX, GOTS or Cradle to Cradle Certified™.

Explore the use of lower-impact processes such as waterless dyeing, natural dyes or digital printing.

Design:

Look to utilise circular design strategies and techniques to eliminate waste and pollution, encourage longer product use, and consider end of life. These include (among others) design for zero waste, durability, and remanufacture.

Use:

Reduce microfibre pollution by choosing certified biodegradable materials.

Encourage customers and wearers to wash on lower temperatures, with fully loaded washes, and use a method to filter fibres (for example with a fibre collection bag or retro-fitted machine filter).

Encourage customers to keep their products in use (either by themselves or by other wearers) through repair, re-sale or donation.

End of life:

Enable a new lifecycle for your materials by developing products that are 100% biodegradable or 100% recyclable.

Encourage customers to return their products to recycling facilities, take-back schemes or composting facilities.

Industry examples:

Icebreaker, a merino wool outdoor and natural performance outdoor clothing brand based in Aotearoa New Zealand, uses high-quality natural fibres to create quality and long-lasting products grounded in environmental sustainability, social ethics and animal welfare.

Ask Nature is an online database founded by the Biomimicry Institute, featuring resources on biological strategies (from breaking down pollutants to creating colour) from the natural world that can be applied to design and innovation in the human world.

How can others start this process?

For students, graduates, designers and fashion professionals who are involved in product development:

Design with nature in mind: evaluate your impact on nature and re-imagine fashion to be regenerative rather than extractive.

Commit to changes at the design and product development phase based on the above considerations.

Map your product or service lifecycle using the framework above, and review the suggestions to select the ones that are most relevant to you.

Make use of existing tools and guides like the CFDA KPI Design Kit, IDEO’s tool database, and the IDEO and Ellen MacArthur Circular Design Guide,

13/18

4. Fashion Practice to Support Biodiversity: Industry Examples

Now that we’ve provided an overview of some of the different ways fashion can support biodiversity, let’s have a closer look at brands that focus on biodiversity as a key part of their approach to sustainability. These industry examples – major luxury fashion brand Gucci, and independent designer Story mfg., focus on protecting ecosystems and regenerating the natural environments their products come from, as well as conservation efforts more broadly.

14/18

4.1 Gucci

Contribution by Gucci

Gucci’s approach to biodiversity encompasses both its business strategy and its collections: the operational and the creative. Their long-term environmental focus was amplified in 2015 via its 10-year “Culture of Purpose” sustainability strategy, which is underpinned by a series of targets to achieve by 2025 and benchmarked against Gucci’s annual Environmental Profit and Loss (EP&L) account. Gucci is dedicated to seriously reducing its footprint along the entire supply chain, and embrace climate-smart strategies to help protect and restore nature for the future. What they can’t reduce themselves, they translate into conserving biodiversity and forests that lessen the impacts of climate change. Three different ways Gucci supports biodiversity include: embedding biodiversity in product, committing to carbon neutrality, and making impactful partnerships.

Embedding biodiversity best practices in product

“Gucci is driven by the issues that are fundamentally influencing our collective future. We are committed to generate positive change for people and for nature across our business.” – Marco Bizzarri, President and CEO

Gucci’s focus on supporting best practices for biodiversity is embedded in the way it designs its products. More sustainable materials are a key focus of this strategy, including cotton grown organically, use of recycled and regenerated materials that minimise the need for virgin fibres, and packaging from sustainably managed forest sources. The brand also banned the use of animal fur in 2018 – one of the first major luxury brands to do so – and has a 100% traceability target for all its raw materials by 2025.

As an example of Gucci’s product efforts, in June 2020 the brand launched Gucci Off the Grid, the first collection under Gucci Circular Lines which features products and collections created with its circular design innovation. Gucci Off the Grid is a collection of five product ranges covering accessories, ready-to-wear and travel pieces made of recycled, organic, bio-based and sustainably sourced materials, including ECONYL® regenerated nylon.

Embedding support for biodiversity in business strategy

Starting from 2018, Gucci has been carbon neutral in its own operations and across the entire supply chain. Gucci follows the mitigation hierarchy, and after avoiding and reducing its greenhouse gas emissions as a priority, Gucci then translates all remaining emissions each year into protecting and restoring critical forests and biodiversity around the world. For 2018, Gucci partnered with REDD+ projects in the Chyulu Hills, Kenya (a volcanic mountain ecosystem), the Alto Mayo forest in the Peruvian Amazonia, Rimba Raya in Indonesia and Southern Cardamom in a tropical rainforest in Cambodia. Gucci is diversifying its 2019 approach and setting up its Natural Climate Solutions Portfolio to include both forest and mangrove REDD+ projects as well as supporting regenerative agriculture and farmers switching from chemically-intensive farming to regenerative farming techniques, which will also support local biodiversity.

Through its parent company, Kering, Gucci is also a signatory of The Fashion Pact, a coalition of fashion and textile companies that aim to mitigate climate change, slow biodiversity loss and protect oceanic ecosystem services. The Fashion Pact provides guidelines for biodiversity-specific commitments, including the development of science-based targets (SBTs) for nature “to assure our contribution to the protection and restoration of ecosystems and the protection of key species.”(26)

Partnerships and creative vision

Gucci’s influential position in the luxury and fashion industry gives them a platform through which to raise awareness for biodiversity topics and issues. Gucci’s aesthetic is inspired by natural motifs, from exotic animals to plant life, creating a visual connection between biodiversity and fashion. Gucci partners with The Lion’s Share Fund, a unique initiative raising much-needed funds to tackle the crisis in nature, biodiversity and climate across the globe. Led by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and a coalition of businesses and UN partners, the Fund’s goal is to raise over 100 million USD every year over the next five years by asking brands to contribute 0.5% of their media spend whenever an animal is featured in their campaigns. Animals appear in approximately 20% of advertisements around the world and the Fund is a creative and innovative concept that organically connects the business community with on-the-ground action to protect wildlife and its natural habitat.

Gucci’s biodiversity focus also includes its home region of Lombardy. A collaboration with Rete Clima, a climate-focused NGO, includes the urban reforestation project ForestaMi, which aims to plant three million trees in Milan by 2030. Gucci’s three-month partnership with The RealReal also supported tree-planting initiatives and for every person purchasing Gucci globally or consigning Gucci in the United States in The RealReal x Gucci shop-in-shop, platform or store, the companies planted a tree through non-profit One Tree Planted.

15/18

4.2 Story mfg

Story mfg. is a British-based, independent vegan brand with a holistic view of biodiversity, founded by Katy and Saeed Al-Rubeyi. Their company philosophy is based on “a desire for a more authentic, fulfilling and kind approach to fashion – one that doesn't involve a trade-off between aesthetics and consciousness.”(27)

As the founding motivations for the brand were intertwined with social and environmental concerns, their work to support biodiversity began on day one, rather than developing strategies or initiatives later on. Story mfg.’s business is based on long-term partnerships with artisans, makers and craft communities from India and Thailand to develop new fabrics, colours and other textile techniques.

Many of the colours used in Story mfg.’s palettes come from natural dyes, some of which are widely used (like Indigofera Tinctoria, natural indigo) and some of which are less common (including babul bark or iron). One of their long-term collaborators, The Colours of Nature, research ancient dye techniques and work with Story to apply them to fashion collections. The India-based company is the largest natural indigo fermentation project in the world.

By restoring traditional techniques to the textiles industry, Story mfg. is able provide a healthy alternative to chemical dyes – many of which can be hazardous and polluting – creating colour out of something that can grow, ferment, decompose, and return to the earth. In the words of co-founder Saeed Al-Rubeyi, “when we make fertiliser out of rotten jackfruit to feed the earth in Tamil Nadu while making a jacket to be worn in California, we feel like we are striking the best balance we can.”(28)

Story mfg. also collaborates on handwoven fabrics with Oshadi, an Indian company that is exploring regenerative practices by bringing back traditional techniques and putting them in use for modern supply chains. While organic generally eliminates the use of hazardous chemicals, regenerative revives native ecosystems and takes care of biodiversity.

Oshadi founder Nishanth Chopra explains that this is about “restoring what was there before… the plants start supporting you.”(29) By growing multiple plants on the same land, cotton-eating species have other food sources to flourish on, eradicating the need for pesticides and hazardous chemicals. He describes regenerative practices as “you create an exchange and you create an ecosystem”.

Regenerative practices, from this perspective, is about more than agriculture. It’s about restoring the rural ecosystems, including networks of insects, plants, birds, craftspeople, dyers, growers, spinners and other artisans – where an ecosystem is a root, rather than a supply chain. As co-founder Katy Al-Rubeyi notes, fashion is gaining a “growing understanding that sustainability is not a lifestyle trend – it’s a fundamentally crucial movement that ties into social inequality, racism, sexism, capitalism, colonialism and modern slavery.”(30)

16/18

5. Applying Biodiversity to Your Own Practice

This Method aims to not only to introduce you to some of the key issues around fashion and biodiversity, but to help you understand how you can begin to address fashion and nature in your own work. In this section we have included some ways you might engage with biodiversity, whether you’re a student, graduate, designer or fashion professional.

So to get you started, use the following questions (aligned with our three programme perspectives: design, media and tech) to reflect on your practice:

Design focus – how can your work help to support biodiversity?

As we covered in section 3.5 above, design has the opportunity to re-frame its relationship with nature – moving from extractive to restorative. But how can you make this shift on a personal level?

Create a brainstorm or diagram that maps the ways your work currently draws from nature. How does it inform your aesthetics? Where do your materials come from – plants, animals, oils, fossil fuels or elsewhere? How does nature support your design process – from your sketchbooks to your laptop? Is there anything in your work that doesn’t draw from nature?

Create a manifesto that focuses on the goals do you want to set in relation to biodiversity. Is your approach to fashion and nature about ‘doing less harm’ or ‘making a positive impact’? What commitments can you make? As we noted earlier, the free CSF online course ‘Fashion and Sustainability: 'Luxury in a Changing World' includes an exercise on developing your own manifesto.

From the perspective of a designer or product developer, where can you see gaps for design processes, practices, materials or other innovations that could better support nature? What do you do currently that could be improved or changed?

Media focus – how can you communicate biodiversity in a creative and engaging way?

While this Method focuses on the design perspective, it’s also an opportunity for media and communications to play a central role in connecting fashion audiences with biodiversity issues and movements.

How can you engage your readers, viewers, followers or audiences with biodiversity and fashion? How can you elicit an emotional response from them in relation to these issues? What new narratives do you want to build around biodiversity?

What are the stories you want to write, the images or videos that you want to create, that could bring biodiversity to life in a meaningful way? Is there anything that you’ve read in this Method that really strikes a chord for you?

How can you platform diverse voices to explore biodiversity topics? What expertise can you draw from that aren’t limited to CEOs or brands? Look to research, read and otherwise draw from the perspectives and work of students, indigenous communities, scientists, politicians, NGOs, artisans, farmers, creatives, councils, and activists. If you engage with them directly (such as through a profile or interview), ensure you are doing so with a clear purpose and informed consent.

Technology focus – how can technology support biodiversity?

Many of the strategies we’ve outlined above are supported by advances in technology, such as blockchain or material innovation (for more information, see our ‘Fashion, Nature and Technology’ Method). What other gaps or opportunities can you think of?

From the perspective of a technology expert or innovator, what expertise do you have that you feel is unexplored by fashion? What are the gaps that you think you could fill?

What is it that you personally want to see change in fashion’s relationship with biodiversity? What are some of the ways your expertise can help contribute to making this change?

What existing innovations, systems or processes (that might be in use in other industries, for example) could be applied in fashion to positively impact biodiversity? What collaborations could bring these to life?

Next steps

Did these prompt questions spark an idea you think could help transform fashion’s relationship with nature? Got the next big idea for fashion and nature? Apply to our Challenge, opening in late March 2021, and become part of a new era in fashion.

17/18

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Francesco Mazzarella, Dr Katrina ole-MoiYoi and the Kering Group for their contributions to this piece.

18/18

Footnotes

1. United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (1992), p.3

6. UN (2019). UN Report: Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating’. (Online)

7. Ibid.

9. Ehrmann, E. (ed.) (2018). Fashioned from Nature. London, UK: V&A Publishing.

10. Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017). A New Textiles Economy.

11. McKinsey & Company. (2020). Biodiversity: The next frontier in sustainable fashion. (Online)

12. Rycroft, N. (2013) Forest-friendly Fashion. The Ecologist. (Online) Available: https://theecologist.org/2013/dec/03/forest-friendly-fashion (Accessible: 13th February 2020).

13. McKinsey & Company. (2020). Biodiversity: The next frontier in sustainable fashion. (Online)

“CanopyStyle,” Canopy, 2020, canopyplanet.org.

15. Krauss, C., Yaffe-Bellany, D., & Simões, M. (2019, Oct 18). Why Amazon Fires Keep Raging 10 Years After a Deal to End Them. New York Times.

16. McKinsey & Company. (2020). Biodiversity: The next frontier in sustainable fashion. (Online)

18. https://www.condenast.com/glossary/environmental-impacts-of-fashion/microfiber-pollution

19. Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017). A New Textiles Economy.

20. https://www.condenast.com/glossary/environmental-impacts-of-fashion#landfill

22. Mazzarella, F., & Williams, D. (2021) Fashion Values Nature: Roundtable Executive Summary.

23. Cernansky, R. (2019). Fashion is Belatedly Trying to Save Earth’s Biodiversity. (Online)

24. https://www.condenast.com/glossary/climate-emergency/regenerative-agriculture

25. Ellen MacArthur Foundation (ASOS)

26. https://equilibrium.gucci.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Fashion_PactG7EN-pdf.pdf

29. https://www.storymfg.com/blogs/essays/podcast-with-nishanth-chopra-of-oshadi

30. https://sourcingjournal.com/denim/rivet-50/2020-katy-al-rubeyi-story-mfg/